In my last post, I discussed how the fear response closely resembles what’s often referred to as the stress response. Given how deeply they are intertwined in the context of work, I wanted to take some time to provide a deeper explanation of their similarities and differences, highlighting how they show up at work.

Fear and Stress Responses

Generally speaking, the fear response is activated by an immediate, identifiable threat—something that presents an actual danger, like the fear of being called out in a meeting or receiving a poor performance review on the spot. It prompts a rapid, sometimes intense reaction designed to protect you in the moment.

In contrast, the stress response doesn’t usually require an immediate threat. Instead, it’s triggered by ongoing pressures or demands, such as looming work deadlines, interpersonal dynamics in the office, or persistent worries about job security. These stressors may not be dangerous in the moment but can accumulate over time, leading to significant mental and physical strain (LeDoux, 2012; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

The Commonalities of Fear and Stress

Fear and stress are both physiological and psychological responses triggered by perceived threats or challenges. They activate similar systems in the body, particularly the amygdala, which leads to increased heart rate, heightened alertness, and the release of stress hormones like cortisol.

Both responses can trigger emotional reactions, such as anxiety, and physical responses, like muscle tension. While fear tends to be tied to an immediate, tangible threat and stress builds up due to ongoing pressures or future uncertainties, both fear and stress prepare the body for action (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

In certain instances, the arousal of fear activates the stress response (Rodrigues et al., 2009), which is why it’s so easy to confuse the two. So how can we differentiate between when we are stressed vs. truly afraid?

Key Differences Between Fear and Stress

While fear and stress share common biological foundations, they differ in important ways:

- Duration: Fear is usually short-lived, subsiding once the threat is removed. Stress, on the other hand, can linger and manifest as either short-term or chronic, depending on how long the stressors persist (McEwen, 2007).

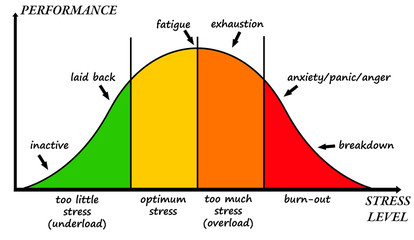

- Function: Fear is about immediate survival—it triggers the fight-or-flight response to avoid danger. Stress helps manage ongoing challenges but can take a toll on your body and mind if not properly managed, eventually leading to burnout (Selye, 1976).

Here’s a real-life scenario to illustrate these differences:

- Experiencing Fear: You’re in a meeting, and your boss asks you to explain your team’s progress. You weren’t expecting to speak, and you feel a surge of panic. That’s fear, as your body reacts to a sudden, immediate challenge. Not exactly a bear in the woods, but you get the idea!

- Stress example: You’ve been juggling multiple projects for weeks, and the deadlines are approaching fast. Each day, the mounting pressure leaves you feeling drained. This is stress, which builds over time due to ongoing demands.

How Trauma Impacts Fear and Stress

Let’s briefly touch on how trauma can complicate our fear and stress responses.

When someone relives a traumatic event, both fear and stress responses are activated. The amygdala triggers fear by perceiving the past event as an immediate threat, while the hippocampus may struggle to differentiate between past and present contexts.

At the same time, the stress response activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing cortisol and intensifying physical symptoms like increased heart rate and hypervigilance.

This dual activation of fear and stress creates a heightened state of emotional and physical arousal, which is common for people experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (LeDoux, 2007; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

For managers, it is critical to understand how trauma affects fear and stress responses to create a more trauma-informed workplace where employees feel supported and safe. Fostering a trauma-informed workplace helps minimize the risk of compounding employee stress with additional triggers.

Workplace Implications: Fear and Chronic Stress

In the workplace, fear and stress are often interconnected, forming a feedback loop that can damage both employee and workplace well-being.

Fear might initially be triggered by specific events—such as the fear of forgetting to remove a “Needs Peer Review” sticker in a client presentation (so I’ve heard), public failure, criticism from a boss, or job loss.

Over time, if these stressors remain unresolved, they can transform into chronic stress, manifesting as ongoing worry, physical ailments, and burnout (World Economic Forum, 2021).

Take the fear of job loss, for example. This can be a powerful motivator in the short term, but if this fear persists, it transitions into chronic stress, leading to decreased productivity and even health challenges (Kalleberg, 2011).

Similarly, repeated fear of criticism or failure in a highly competitive work environment can lead to long-term stress, resulting in burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

Fight-or-Flight in the Workplace

As alluded to earlier, the term fight-or-flight is often used interchangeably for both the fear response and the stress response because they trigger similar biological systems. Both reactions activate the sympathetic nervous system, releasing cortisol and adrenaline to prepare the body for action (LeDoux, 2012; McEwen, 2007).

Here’s how that plays out in the workplace:

- Fear: You get called into your manager’s office for an unexpected performance review. The sudden, identifiable threat triggers a fear response—maybe you get defensive (fight) or feel like you want to shrink back (flight).

- Stress: Now imagine trying to manage multiple deadlines without much support. Then add in a sprinkle of ambiguity, and sudden changes in demands and–Presto! We have burnout. In other words, over time, the stress response keeps your body in a constant state of fight-or-flight, leading to strain, exhaustion, and sometimes burnout (see below). You might push yourself to work harder (fight) or disengage and procrastinate (flight) (Chrousos & Gold, 1992; APA, 2022).

What Can Managers and Employees Do?

Understanding the difference between fear and stress can help leaders and employees navigate workplace challenges more effectively. Here are a few practical steps:

- For Managers: Avoid creating environments where fear is the default motivator. Offer regular feedback to prevent fear-based surprises and provide resources for managing long-term stress, such as clear expectations, support for workload management, or access to mental health services.

- For Employees: If you find yourself stuck in chronic stress, consider practices like mindfulness, time management strategies, or talking to your manager about workload distribution.

Conclusion

Fear and stress may share biological pathways, but they differ in how and why they’re triggered. While fear is about immediate threats, stress comes from ongoing pressures. By understanding the difference, managers can create healthier work environments where acute fear responses are minimized and chronic stress is managed effectively.

Before next time: Think about your own workplace experiences. Have you ever confused fear for stress or vice versa? How do you manage each?

References:

- LeDoux, Joseph E. The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster, 1998.

- Phelps, Elizabeth A., and Joseph E. LeDoux. “Contributions of the Amygdala to Emotion Processing: From Animal Models to Human Behavior.” Neuron, vol. 48, no. 2, 2005, pp. 175-187. Link to article.

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company, 1984.

- Rodrigues, Serafim M., Joseph E. LeDoux, and Elizabeth A. Phelps. “The Influence of Stress Hormones on Fear Circuitry.” Neuropharmacology, vol. 57, no. 3, 2009, pp. 194-199. Link to article.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 87, no. 3, 2007, pp. 873-904. Link to article.

- Selye, Hans. The Stress of Life. McGraw-Hill, 1976.

- Kalleberg, Arne L. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. Russell Sage Foundation, 2011.

- Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. “Burnout: A Brief History and How to Build Resilience.” Burnout Research, vol. 3, no. 4, 2016, pp. 198-209.

Link to article. - Chrousos, George P., and Philip W. Gold. “The Concepts of Stress and Stress System Disorders.” JAMA, vol. 267, no. 9, 1992, pp. 1244-1252.

Link to article. - American Psychological Association. Stress in America: 2023 Report. American Psychological Association, 2023. Link to report.

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2021. 16th ed., World Economic Forum, 2021. Link to report.