In short, we fear to survive. Our fear response has been crucial to humanity’s evolution, significantly influencing our ability to respond to threats and adapt to changing environments.1

Why Fear? A Quick Backstory

I decided I wanted to look into fear a couple of weeks ago after an interaction with my daughter.

She was home one day from daycare and wandered out of sight into the other room. I found her covering her face. I initially chalked this up to normal business toddlers get up to when they go into hiding.

When I asked her what was happening, she said, “Daddy, I’m scared.”

After some back and forth, we figured out she was scared of a toy dinosaur that has been in our hallway for what seems like forever (why this is there is an entirely different topic for another blog).

Understanding the basics of fear (e.g., its origin, purpose, typical impact, etc.), I had some inkling about the situation, but this raised some new questions for me.

- Why was she afraid?

- How did this fear develop?

- Why was I not afraid?

- How do we understand this better to address the fear?

After sitting with these questions for a few days, I started to pull at the thread and do a little research to better understand—in general—why we fear and where it comes from.

As I read, I realized that there is no time like the present to explore fear in the context of our social systems and work. This post will dig into the background of fear, beginning with a brief history.

The Evolution of Fear: A Brief History

To truly understand fear, we need to go back approximately 600 million years. Early life forms, such as jellyfish and worms, had simple neural networks capable of responding to harmful stimuli.2,3 Fast forward to around 500 million years ago, and vertebrates—our ancestors—began developing an early form of the amygdala, the brain structure responsible for modern fear responses.4

As we evolved, particularly between 2.6 million and 11,700 years ago, the fear response in humans began to anticipate danger and learn from past experiences.5,6

When human social groups formed around 200,000 years ago, fear became intertwined with social dynamics.7 Rejection from a group and tribal conflicts emerged as new forms of threats. During this time, our fear of social exclusion became more entrenched; our need for acceptance by others became necessary for survival.8

As populations grew, tribes formed and began competing for limited resources. Many believe that competition around this time fostered a zero-sum, “us vs. them” mentality, where survival depended on out-competing other groups. In this environment, the need for belonging became critical, heightening the fear of being cast out or facing conflict with other tribes.8

Around 10,000 years ago, as modern civilization began to take shape, fears surrounding social status, competition, and securing resources became increasingly prevalent. What’s remarkable about our timeline is that social structures and the need for belonging as essential elements of survival were established long before the emergence of organized civilization.9

Our deep-rooted need for social inclusion and belonging remains a basic human drive. In the U.S., the fear of social exclusion is a common tool of influence—just turn on the television. Politicians often tap into this evolutionary predisposition, leveraging fear to drive campaigns that push us to align with particular groups as a way to ensure our sense of security and survival. (Apologies, but I can’t ignore the elephant and donkey in the room).

While the physical threats that once endangered us have largely faded, our fear circuitry remains. Instead of predators lurking in the brush, we now face more complex social and psychological threats—such as rejection, job insecurity, and financial instability. While the core mechanism of fear remains relatively unchanged, the nature of our fears has evolved.10, 11, 12

The Complexity of the Modern Fear Responses

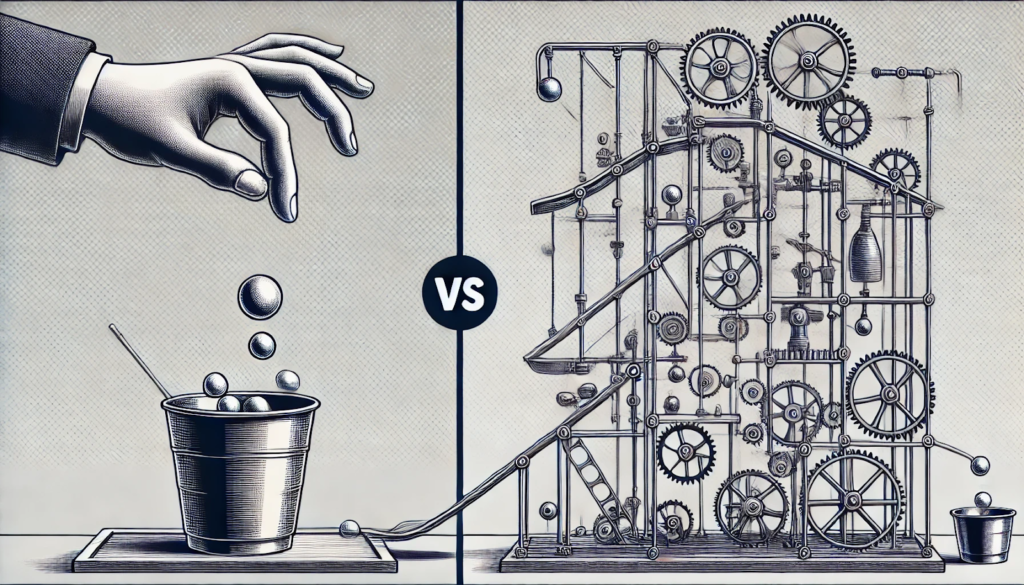

The simplicity of ancient fear responses has evolved into a far more intricate process. When I think of this evolution, I think of our distant ancestors’ response as the simple act of dropping a ball into a cup. On the other hand, the modern response seems more like a Rube Goldberg machine: complex, with interdependent steps that can send the ball on its way to the cup (with an equal amount of opportunities for things to go off track).

Although the basic response remains—our brain detects a threat and responds—modern fear is shaped by a web of cognitive processes, including emotions, past experiences, and societal expectations. What’s particularly striking is that these perceived threats don’t need to be real or immediate, as they were for our ancestors. Our brains can still react just as powerfully to imagined or potential dangers, triggering the same intense fear response we once relied on for survival from imminent danger.13

When we think about modern fear, I believe Brene Brown defines it perfectly in her sensational book, Atlas of the Heart. Dr. Brown writes,

“Fear is a negative, short-lasting, high-alert emotion in response to a perceived threat, and, like anxiety, it can be measured as a state or trait. Some people have a higher propensity to experience fear than others.

Fear arises when we need to respond quickly to physical or psychological danger that is present and imminent. Because fear is a rapid-fire emotion, the physiological reaction can sometimes occur before we even realize that we are afraid.”

Brown’s research also highlights that the fear of social rejection is on every list of fears she has encountered in her research (more on this later).

She continues by sharing words from Dr. Harriet Lerner, “Throughout evolutionary history, anxiety and fear have helped every species to be wary and to survive. Fear can signal us to act, or, alternatively, to resist the impulse to act. It can help us to make wise, self-protective choices in and out of relationships where we might otherwise sail mindlessly along, ignoring signs of trouble.”

At the core of this process is the amygdala, a small but powerful part of the brain that plays a critical role in how we experience fear. The amygdala’s rapid response to perceived threats—whether real or imagined—is what allows us to react in an instant, even before we fully process the danger. But as our understanding of fear has evolved, so too has the amygdala’s influence on more abstract fears, such as social rejection or failure.15 Let’s explore how this ancient structure continues to shape our reactions in the modern world.

The Amygdala at Work: Fear and the Workplace

In the workplace, our fear response plays a crucial role in how we handle high-pressure situations.

Stress-inducing stimuli—like tight deadlines or unexpected challenges—trigger the amygdala’s fight, flight, or freeze response.16

However, thanks to the prefrontal cortex, we have the ability to regulate this reaction, allowing for more measured and thoughtful responses.17

This biological process is particularly important in fast-paced environments where quick decision-making is vital. Leaders who understand this mechanism can better manage fear in themselves and their teams, fostering resilience and promoting a healthier, more productive workplace.18

Fear Response and Social Isolation: A Cycle of Disconnection

At its core, social isolation exacerbates fear, and the fear of social isolation helps us maintain our ties to others. As previously mentioned, humans evolved to exist within communities, relying on social bonds for protection and survival. In modern society, social isolation may no longer signal immediate physical danger, but it triggers psychological fears—loneliness, abandonment, and uncertainty.19

This disconnection can manifest in various ways, especially in the workplace. Remote work, hierarchical structures, and cultural marginalization can all create a sense of isolation that heightens fear and anxiety, meaning our behavior can lead us to avoid situations and people that create these feelings, thus forging deeper disconnection. Alternatively, as we look to maintain social connections, we see resulting behaviors such as masking, which can lead to a host of issues like moral injury, burnout, and disintegration from our beliefs and values.

The solution lies in reconnection and inclusivity—both with others and with our authentic selves. We will explore how to foster inclusive environments and align work with personal values to better support our organizations’ abilities to mitigate fear and promote emotional well-being later in this series.20

Final Thoughts

Why do we experience fear? Fear has created advantages to individual survival and has driven the survival of our species. Throughout our evolutionary history, fear has played a significant role in shaping our emotional and social development.

Understanding the origins of fear and its complexities in today’s world can help us effectively manage it in both our personal lives and workplaces. By using our biological responses and nurturing meaningful connections, we can harness fear as a catalyst for growth, adaptation, and innovation.

I touched a little here on fear in the workplace, but I will explore this in additional detail in my next post.

Throughout October, I will share each post directly with my LinkedIn network. However, feel free to use the box below to subscribe and have each installment sent directly to your email inbox. Have comments? Let’s start a conversation here.

References

American Psychological Association. Review of General Psychology. American Psychological Association, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-295X.108.3.483. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Perini, Julie. “The Wonders of Jellyfish.” Caltech Magazine, https://magazine.caltech.edu/post/the-wonders-of-jellyfish. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Günter, Matzdorf, et al. “Dynamic Capabilities and Their Role in Innovation.” Innovation and Development in Business Systems, edited by Dirk Fornahl and Christian Zellner, Springer, 2016, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-43685-2_3.

De Neys, Wim. “Bias and Conflict: A Case for Logical Intuition.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 4, 2013, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00667/full. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Nesse, Randolph M. “Evolutionary Origins of the Affective System.” The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Emotion, edited by Todd K. Shackelford, Oxford University Press, 2019, https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/56886/chapter-abstract/455229632?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Pleistocene Epoch.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/Pleistocene-Epoch. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Smith, John P., et al. “Psychological Models in Education.” Educational Psychology: Models and Practices, edited by James N. Furze, Springer, 2021, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-91010-5_15.

Hanson, Jason. “Behavioral Economics and Emotional Regulation.” The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Economics, edited by Todd K. Shackelford, Oxford University Press, 2023, https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/34460/chapter-abstract/292372929?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

Cartwright, Mark. “Dynamics of the Neolithic Revolution.” World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1937/dynamics-of-the-neolithic-revolution/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Conway, Robert. “The Influence of Workplace Stress on Health.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 14, 2023, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1321053/full. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Worrall, Simon. “What Happens in the Brain When We Feel Fear?” Smithsonian Magazine, 29 Oct. 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-happens-brain-feel-fear-180966992/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Joseph, Simone. “Cognitive Load and Its Implications for Mental Health.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 2021, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727363/full. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Worrall, Simon. “What Happens in the Brain When We Feel Fear?” Smithsonian Magazine, 29 Oct. 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-happens-brain-feel-fear-180966992/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Brown, Brené. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. Random House, 2021.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “Stress and the Fight-or-Flight Response.” ScienceDaily, 27 Mar. 2001, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/03/010327080532.htm. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Health Centre NZ. “The Science of Stress: Understanding the Fight-or-Flight Response.” Health Centre NZ, https://healthcentre.nz/the-science-of-stress-understanding-the-fight-or-flight-response/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

ScienceDirect. “Prefrontal Cortex.” ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/prefrontal-cortex. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Darden School of Business. “How Leaders Build Resilience.” Darden Ideas to Action, University of Virginia, https://ideas.darden.virginia.edu/how-leaders-build-resilience. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

University of Chicago. “How Social Isolation Affects the Brain.” Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, https://psychiatry.uchicago.edu/news/how-social-isolation-affects-brain. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Santos, Liza M. “Resilience in Education and Learning Development.” The Dynamics of Learning and Development, edited by Maria G. Baldini, Springer, 2022, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-10788-7_5. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Pingback: Fear and Stress Responses: Their Impact in the Workplace - Josiah Conrad, MPH, CHES

Pingback: Fear is Universal? - Josiah Conrad, MPH, CHES