Moving the Workplace Forward

Fear and the Workplace: A Look Back

It’s scary to think that tomorrow is November, but we covered a lot of ground this month. If you stuck with me throughout October, you likely picked up on my desire to truly understand something before diving into strategies and tactics to address the challenge. In my opinion, if we don’t dig deep enough into something, we can only dive into the shallow end.

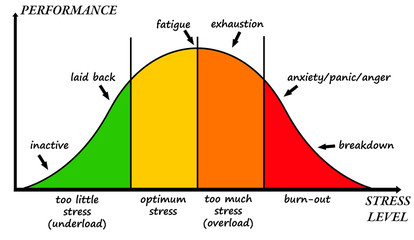

When introducing this month’s topic, we discussed how fear evolved from a primitive survival mechanism to something that can affect our emotional experience and behavior. We also took a look into the intermingling of fear and stress and how they show up at work.

Then I was stumped. I couldn’t bring myself to proceed with my original outline, taking me back to the drawing board. I didn’t want to head into various strategies and tactics that aimed to disarm fear in a uniform way. There was this overwhelming sense of urgency to highlight that fear is incredibly nuanced; our identities and experiences shape our fear responses.

Today, we’ll discuss strategies for mitigating fear in the workplace and some of the consequences if it’s left unchecked. However, it’s essential to recognize that fear is deeply personal, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. To effectively address fear—both in yourself and in supporting others—you must take the time to genuinely understand individual perspectives and experiences. This can be challenging in a professional setting, where we must balance empathy with the demands of the job, but building this understanding and forging genuine human connection is critical for creating meaningful, supportive solutions.

So, fear in the Workplace…

You’ve been there before. Your heart is pounding, your mind is racing. The rush of blood through your system thumps in your ears. Your neurons are sending a chaotic stream of sensations through your body. Just a few seconds to make a move. For all you know, it could be your last.

A bead of sweat grazes your forehead and suddenly, it’s clear: this isn’t life or death, but right now, it feels like everything. As you click send on the email, you begin to run your floor routine of mental gymnastics flipping, twisting on every word in your report, and how it may affect you and your survival. It’s as if life hangs in the balance of the age-old question: Did you use too many exclamation points in your email?

Then you hear the three quick knocks come through your speakers before you can see it. Funny how workplace chat notifications always seem to come like lightning and thunder that way.

Since it’s Halloween you can choose your own adventure to see how this plays out in a workplace marred by fear and how this plays out in workplaces with more supportive cultures.

Workplace fears—concerns like job security, speaking up, and judgment—are real and powerful. They’re not just personal concerns but commonplace when operating in high-stakes environments. And these days, it seems like everything is high stakes. Let’s look at these more closely.

Fear of failure and job insecurity includes concerns about making mistakes or facing criticism. This can lead to anxiety and lower productivity. This fear often discourages employees from taking risks or suggesting new ideas, limiting innovation and growth.

Fear of speaking up generally manifests when employees feel they can’t safely express opinions, voice concerns, or offer dissent. It reduces open communication, feedback, and adaptability across the organization.

Fear of Judgment and Exclusion is tied to our human need to belong. The worry about being judged, excluded, or undervalued in the workplace can drive self-censorship and silence. This diminishes creativity and a sense of belonging in teams.

These fears don’t merely affect individuals; if unaddressed, they corrode trust, stifle collaboration, halt innovation, and make organizations less adaptable and resilient in the face of change.

Addressing Fear in the Workplace

To address these common yet pervasive workplace challenges, I’m adapting the socioecological model to explore fear at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. This approach helps build psychological safety and inclusion, essential elements for reducing fear in the workplace. Living in a swing state this close to an election, I will stay away from the broader dimensions focusing on society/policy (but a friendly reminder to vote).

Let’s break it down level by level!

Individual

At the individual/intrapersonal level, fear is shaped by personal characteristics, experiences, and psychological factors, such as past experiences and trauma, self-efficacy, and resilience among other things. In the workplace, employees bring their unique fears—whether of failure, rejection, change, or the unknown—based on these personal histories and traits (See more about the personal aspects of fear here).

Some ways organizations can mitigate/address these individual-level fears include:

- Creating or refining mentorship programs

- Encourage skip-level meetings (and have leaders initiate them)

- Normalize ongoing feedback and development coaching

- Conduct goal-setting and role-clarity exercises to reduce ambiguity

- Celebrate effort and learning over output and outcomes

- Involve employees in decision-making processes that impact their work

People who know their organization has resources for growth and development tend to fear failure less than those who believe mistakes could end their careers. Knowledge of support systems reduces fear because it offers a buffer against potential negative outcomes.

Essentially, when individuals feel equipped and supported, their personal fears become less overwhelming.

Interpersonal

You will notice that these strategies require interpersonal connections in the workplace. As we look at addressing fear at the interpersonal level, let’s look at workplace relationships.

Relationships with colleagues, managers, and mentors play a significant role in influencing fear responses at work. Trust, communication, and support (or lack thereof) within teams can either alleviate or exacerbate individual fears. For example, fear may increase in a team environment with low psychological safety, where people feel judged or unsupported.

Employers can train managers and team leaders to recognize and reduce fear-based dynamics by fostering open communication, constructive feedback, and a non-punitive approach to mistakes. Encouraging mentorship and peer support networks can also provide employees with trusted sources of guidance and reassurance.

Organizational

At the organizational level, we look towards organizational culture, policies, and structures that shape how fear is collectively experienced and managed. An organization’s attitudes toward failure, risk, and transparency have an outsized influence on employees’ comfort in taking initiative, sharing ideas, or challenging the status quo.

Fear-reducing practices include establishing clear, fair policies on performance and feedback, as well as promoting a growth mindset where failures are treated as learning opportunities. Additionally, transparency in decision-making and a consistent application of values contribute to a predictable environment that minimizes fear of ambiguity and uncertainty.

I fear we’ve reached the end

In every organization, fear exists—and that’s normal. What’s not normal, or sustainable, is leaving it unchecked. Fear at work can hinder creativity, collaboration, and overall well-being. As we’ve explored, fear doesn’t respond to blanket solutions; it requires a thoughtful approach that takes into account the individual, relational, and organizational dynamics that shape each employee’s experience.

Facing workplace fears means actively addressing them at each of these levels. At the individual level, we can support employees with clear feedback, development-focused coaching, and inclusive goal-setting. Interpersonally, managers and peers can foster trust and open communication, creating spaces where people feel safe to voice concerns and take risks. Organizationally, we need structures and policies that celebrate learning, respect diversity, and enable transparency.

Let’s move forward together. This isn’t just about removing fear but about creating something better in its place—a culture of safety, belonging, and resilience. Reflect on where fear might be limiting your team and consider the strategies we’ve discussed here. Start conversations, make incremental changes, and build that supportive culture where every employee feels empowered to bring their whole self to work.

So here’s the challenge: Take one action this week to address fear in your workplace. Whether it’s a one-on-one conversation, a team check-in, or providing feedback on a policy, every small step counts in creating a workplace where people thrive, not just survive. Let’s work toward a future where courage and growth replace fear and limitation.

To bring our series to a close, if we work to understand what drives our fears we can figure out how to address them, after all a behavioral reaction could be fear of the dinosaur or fear of the dinosaur getting cold sitting by the door, and maybe. Just maybe, you might have four ways to fix that issue.